Getting Started with Shore Diving in the NYC Area

INTRODUCTION

Our dive club has a number of resources about diving in the New York City area, including a guide for people just getting started, focused on boat diving and the offshore wrecks. This article is about shore diving in our area. Check out the gallery below for some photos, as well as a video at the bottom of the page showing what diving is like at the Manasquan River railroad bridge. And feel free to get in touch if you have specific questions!

- Michael Rothschild (New Jersey dives, underwater images and video)

- Harris Moore (Ponquogue Bridge and Beach 8th Street dives)

- Special Thanks to Bill Cadden, Adam Schneider and Meredith Massey

Our dive club has a number of resources about diving in the New York City area, including a guide for people just getting started, focused on boat diving and the offshore wrecks. This article is about shore diving in our area. Check out the gallery below for some photos, as well as a video at the bottom of the page showing what diving is like at the Manasquan River railroad bridge. And feel free to get in touch if you have specific questions!

- Michael Rothschild (New Jersey dives, underwater images and video)

- Harris Moore (Ponquogue Bridge and Beach 8th Street dives)

- Special Thanks to Bill Cadden, Adam Schneider and Meredith Massey

LOADING

SHORE DIVING

Our charter boat dive trips are amazing, with many historic shipwrecks to explore. And while these dives are deeper with typically better visibility, larger sea life and often fascinating back stories, shore diving has a number of advantages over boat diving.

First of all, once you have your gear, shore diving is very cheap – the cost of an air fill – while charter spots are usually $100-$200. Also, you are not dependent on anyone else’s schedule, only the tides determine when you can dive. The boats stop going out in the off season (December – April), but the ocean is always there. There are no issues with sea sickness, and no cancelled dives due to big waves.

The shallow water is usually warmer as well. While I always wear my dry suit for boat dives, I dive my 5mm wetsuit year-round off the shore. A boat dive typically takes up at least half of a day, requiring you to be at the dock before 6 AM, and not returning until the afternoon. Shore diving can be done in an hour, with plenty of time to enjoy other topside activities with your non-diving friends and family.

Night diving is an incredible experience - animals that hide during the day are out and about after sunset. Bioluminescence is also amazing, and I have seen this in New Jersey. The charter boats very rarely do night dives, but when high slack tide lines up with a reasonable time of the evening, try a night shore dive. Dawn and dusk diving is also an option when the tides are right, it's a lot of fun to watch the undersea world wake up.

One issue with shore diving is that most of them are tidal in nature. While there are a few dive sites directly off the coast in the open ocean, most of these have been covered with sand in recent years, and there is little sea life on the open sandy bottom. Therefore, our shore sites are typically ocean inlets, where the clear sea water floods upstream twice a day, giving the best dive window with minimal current, greater depth and better visibility at “high slack." We are not concerned with low slack, as the water is generally dirtier, with poorer visibility due to the bays and estuaries draining into the site.

Any shore diver should have an app that shows the local tides. Also, the pages below have the tide tables embedded in them for each dive site. Depending on the location of the site and the width of the inlet, getting in the water at the wrong time can be anything from barely noticeable to a significant risk of catastrophe. I will go over specific dive sites later on in this article, but for the most part, it is best to plan your dive around slack tide, both for safety and for visibility.

Tidal water motion follows a cycle, which repeats twice each day. High tide is when the incoming sea water results in the greatest depth, and low tide is shallowest. Slack tide just means that the water stops moving in or out, and there is no tidal flow at all. Generally, high and low tides correspond with slack tide – the ocean floods inwards upstream, raises the water level, and then flows back out to sea with the water level dropping until low tide is reached.

However, there are some situations related to local geography where high tide and slack tide are at slightly different times. In some cases, the tidal station (where the tides are observed for the purpose of creating the tables) is different than the dive site. The more you dive a particular location, the more familiar you will become with these subtle, yet very important, nuances.

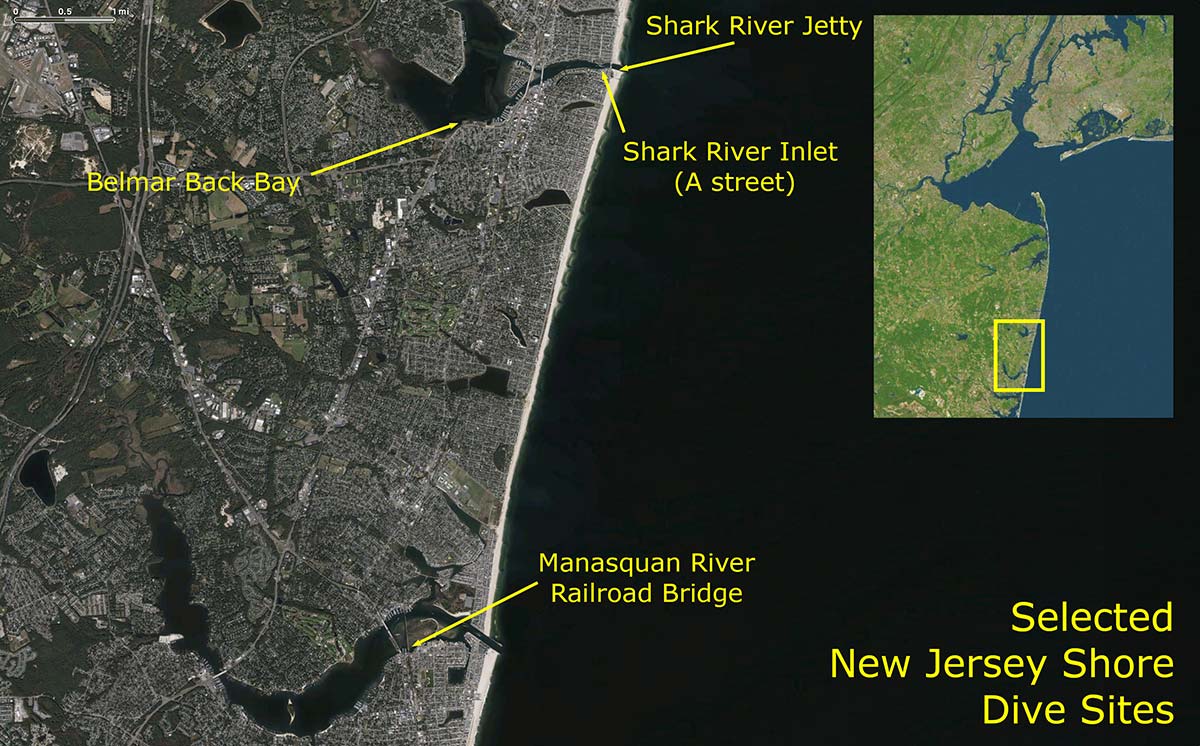

Tidal water flow is inversely proportional to the width and depth of the channel. Since the same amount of water has to move through all parts of the inlet during any given time period, it moves faster through narrow passages. An example of this at the Jersey shore would be the Manasquan River railroad bridge, where the streambed is narrow between the abutments. This means that a diver who stays long past slack tide will be squirted eastward at high speed past the piers as the current builds. On the other hand, the Belmar Back Bay is very wide, so the current is rarely an issue, no matter when you enter the water. For some dive sites (like the Shark River jetty), miscalculating your dive timing can mean being swept out to sea.

Typically, you want to plan your dive so that you enter the water as the tide is still flowing upstream, maybe 20-30 minutes before high slack. That means that you will have about an hour, centered on the still water of slack tide, with a small amount of current before and after that. If you need to swim against the current, you will have an easier time of it.

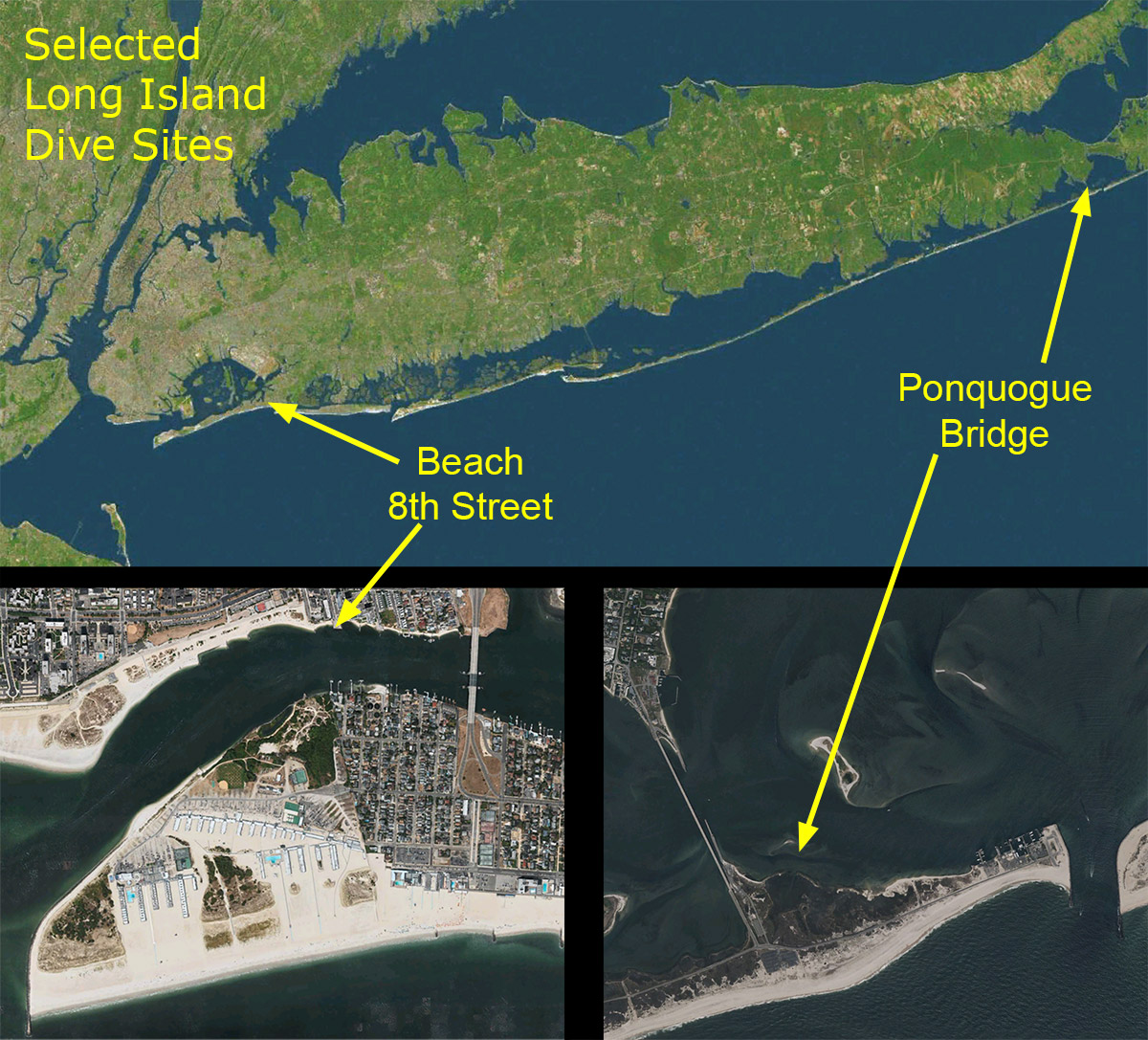

Some of the New Jersey sites (like the railroad bridge or the Belmar Back Bay) are open to divers 24/7, 365 days a year. For others with heavy boat traffic, diving is not allowed during peak boating hours. On Long Island, the three tidal sites (Beach 8th Street, Oak Beach Marine Park, and the old Ponquogue Bridge) all border active boating channels. While diving is not restricted here, situational awareness is paramount.

Site access can vary. The Jersey shore really welcomes divers; there are no issues with parking permits. Street parking is available and safe, and some sites have parking lots. Local groups have even built equipment tables at some of the Jersey sites specifically for divers, to help people gear up. At Ponquogue Bridge on Long Island, parking permits are required due to the proximity to the main bathing beach for Hampton Bays.

While local ordinances vary from town to town in New Jersey, there are a few that pertain to diving that are important to know. In general you are required to tow a surface float with a dive flag, to alert boat operators of the presence of a diver in the water. They in turn are restricted from operating near such a flag.

I prefer a foam float with a tall flag stick for best reliability and visibility - an inflatable float can be punctured and is not as easily seen. I use a small reel to tow the float. This is much better than the cheap plastic frame that comes with many of these, for quickly releasing or tightening up the line, and for adjusting the length of the tow underwater. To keep both of my hands free, I lock the reel and clip it off to a hip D-ring with a bolt snap. If you do this, put a "breakaway" in the line in case the flag or the line gets snagged by a passing boat. A tank O-ring works perfectly for this, just tie the reel to the O-ring and the O-ring to the bolt snap.

In New York state, not only does every municipality that borders the ocean have ordinances AGAINST Scuba Diving, the sport is also outlawed in the entire state park system. However, each regional park system can make their own exceptions to the rules. The Long Island Region does have a “Regional Scuba Permit” for diving in 4 of the State Parks on Long Island.

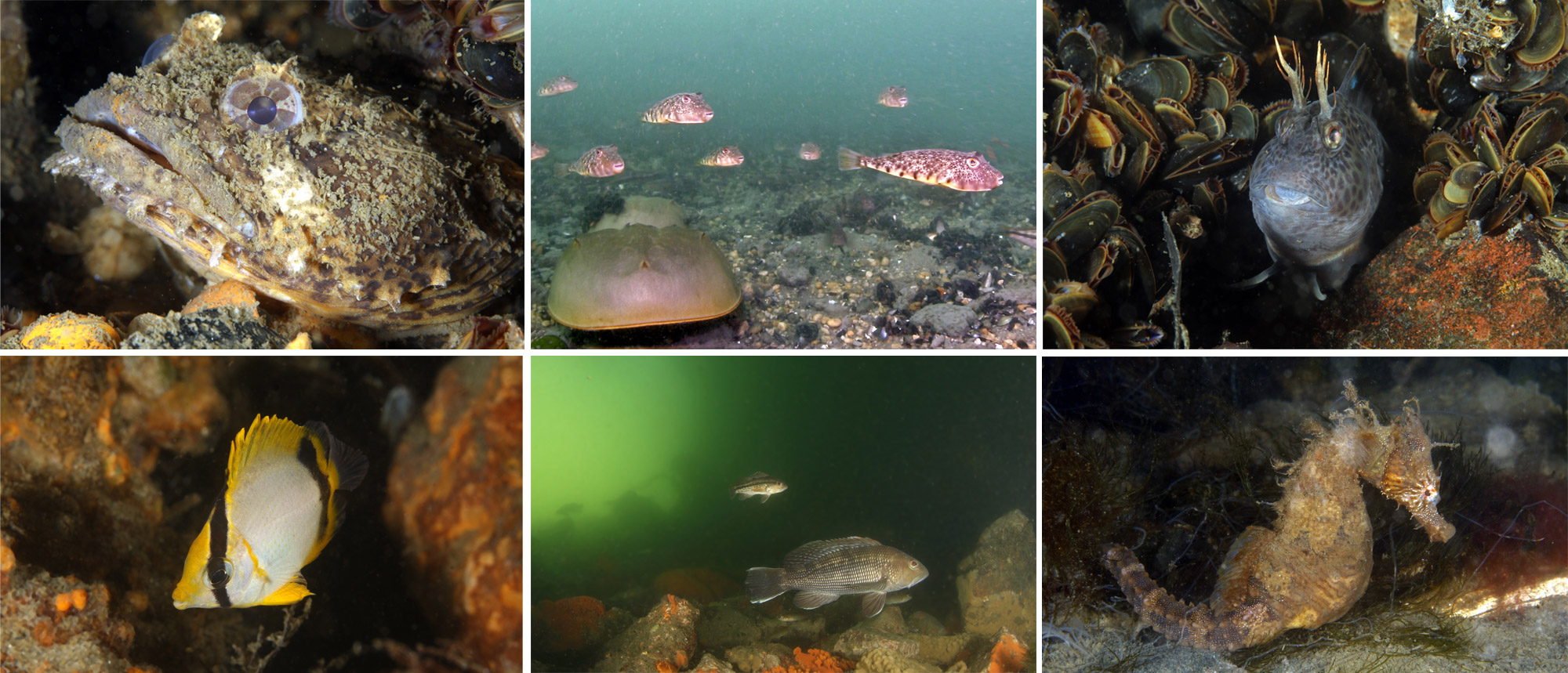

While the shore dive sites sometimes have excellent visibility, this is the exception rather than the rule. That doesn’t mean you can’t have a great dive on most days. Even on days where visibility is particularly bad, I have had a lot of fun doing “muck diving” to photograph the smaller residents of the area. If you like, there are some online groups where people routinely post visibility reports so that you can make a decision before driving to the site.

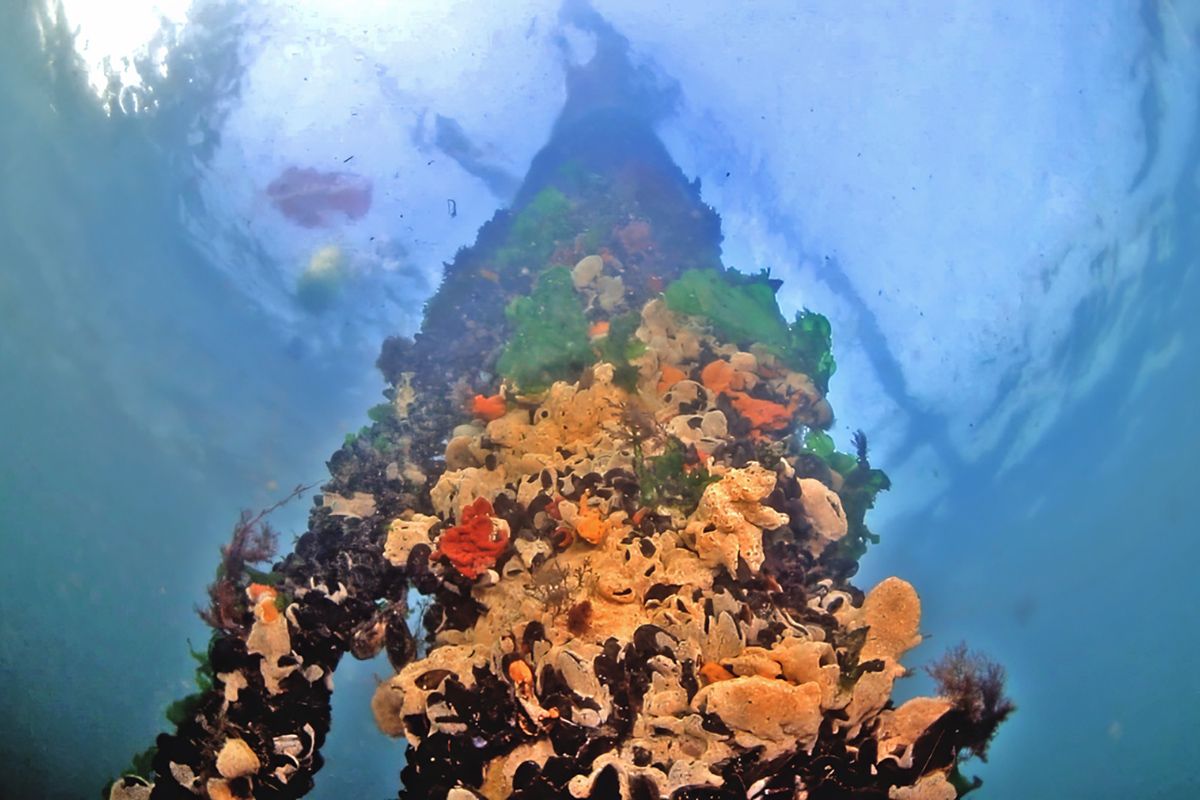

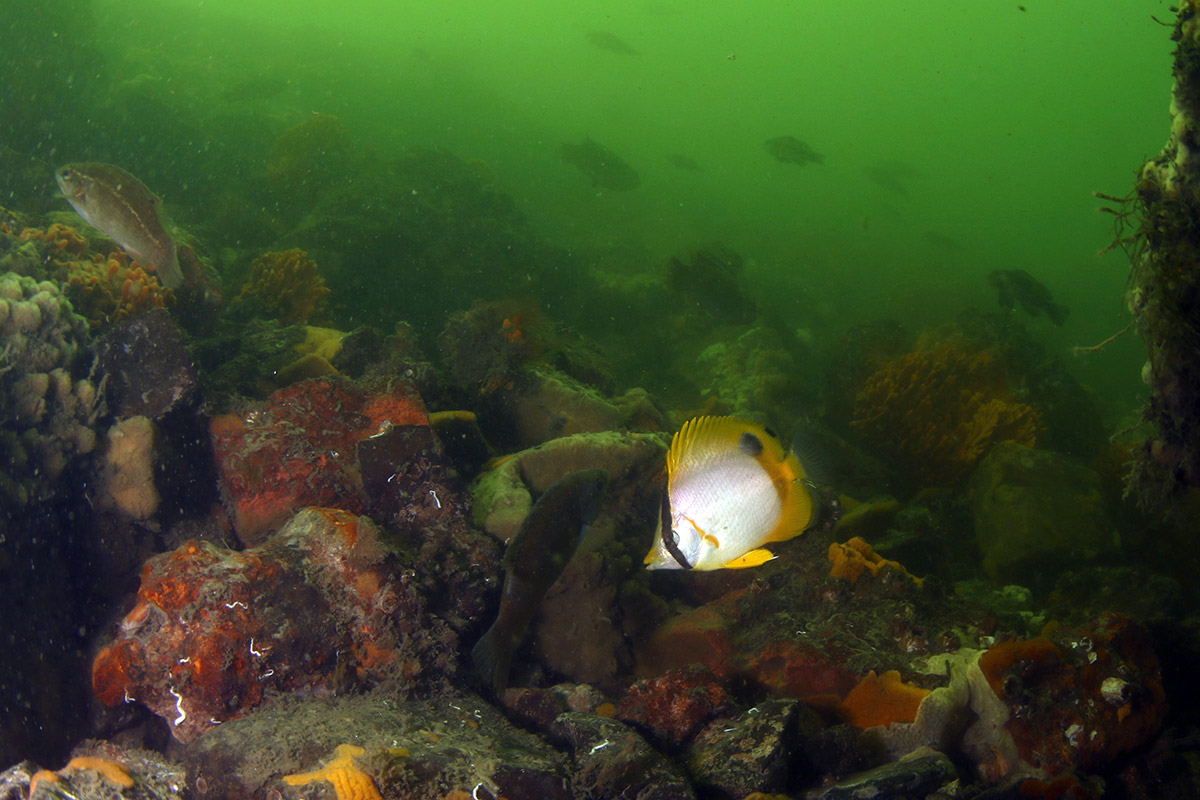

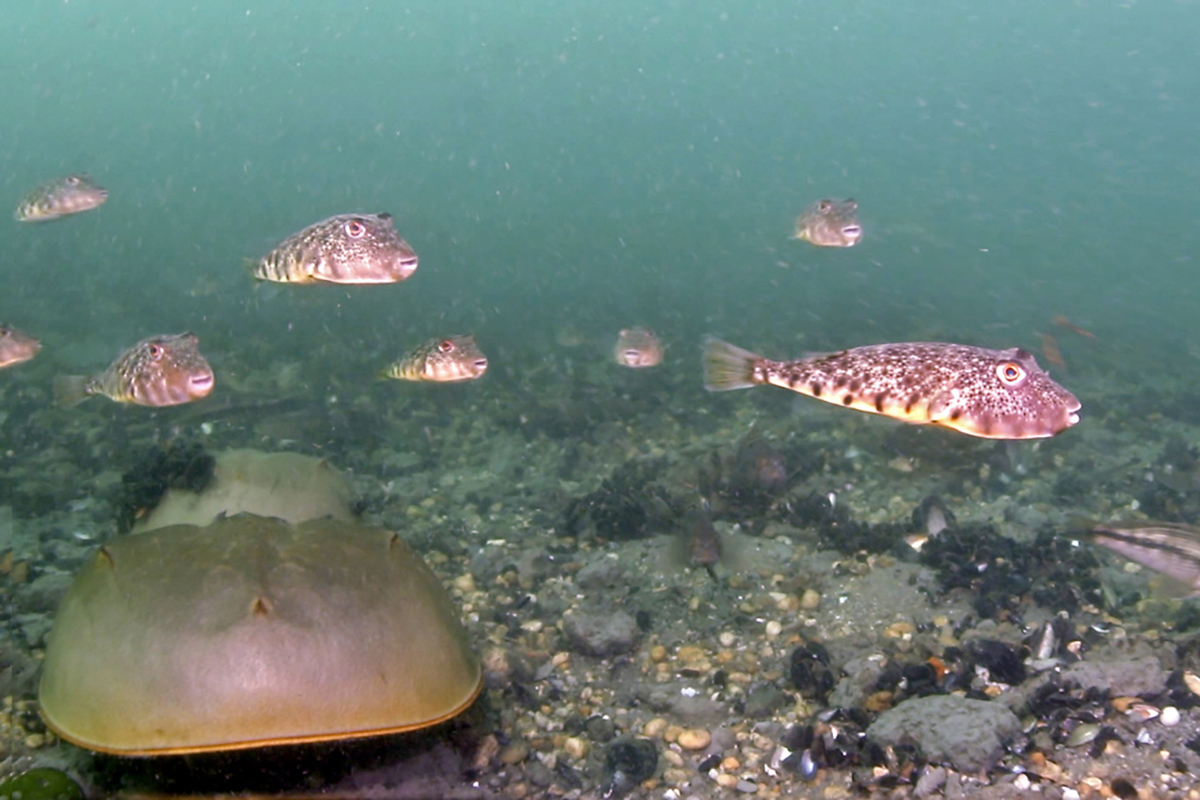

Macro photographers and other divers prepared to explore the nooks and crannies of these healthy, vibrant marine environments will not be disappointed. In late summer and early fall, not only are the sites dripping with life, but many tropical species which come north on the Gulf Stream can be found. Visibility is often much better in the cold weather of winter and early spring, but there is less obvious sea life to be seen at those times.

Like for all NYC area dives, two cutting devices should be carried, as you may encounter discarded fishing line and other entanglement hazards. I recommend a trauma shears carried on a harness or other BC attachment. These are cheap and incredibly strong – they can cut heavy rope or wires. Unlike a dive knife, they can be used with minimal risk of injury, even in a panic situation. As a backup, I carry a Trilobite line cutter on the wrist strap of my dive computer. Remember, you may well be sharing a dive site with people who are fishing, and those lines and hooks can end up in your path. It’s not common, but it is possible to get snagged – it happened to me.

Nitrox is unnecessary for these dives, depths are typically less than 20 feet. While a redundant gas supply is often used on boat dives in our area, this is generally not needed for shore diving given the proximity of the surface. A light is a good idea, as there are plenty of small holes to explore. And if you are diving in an area where getting swept away on the current is a potential risk, carry signaling devices (such as a whistle and/or a rescue GPS). And a mesh bag can be useful to help you carry any trash or artifacts you might pick up.

Finally, a compass is very important - it's easy to get lost or disoriented when you aren't on something like a big wreck. While you can navigate by sensing the current, watching the falloff of the bottom depth or following undersea structures (like the inlet seawall), a compass will help you find your way home and avoid ending up in an active shipping channel.

I lock my wallet and phone in my car using the waterproof "valet key" which is detachable from many modern electronic key fobs. I just put the key in my bathing suit pocket, under my wetsuit, where it can't get lost. For people who have electronic keys and no valet key option, the options are to bring a reliable waterproof case (be sure it's secure!), or hide your key somewhere on or near your car.

A supply of fresh water is useful to shore divers, to rinse off sand before loading your car, as is a small tarp or beach mat to stand on while suiting up and gearing down.

Now let’s go over some specific dive sites! Click on the photos below for information and tide tables for sites on the Jersey Shore and Long Island. This site describes the ones that we have the most experience at, but there are a lot more than these if you want to explore. Club member Danny Rivera has an excellent book on diving on Long island, as does former club president David Rosenthal. For New Jersey sites, check out the book by Daniel and Denise Berg, or the one by Tom Gormley and Ben Gualano.

Our charter boat dive trips are amazing, with many historic shipwrecks to explore. And while these dives are deeper with typically better visibility, larger sea life and often fascinating back stories, shore diving has a number of advantages over boat diving.

First of all, once you have your gear, shore diving is very cheap – the cost of an air fill – while charter spots are usually $100-$200. Also, you are not dependent on anyone else’s schedule, only the tides determine when you can dive. The boats stop going out in the off season (December – April), but the ocean is always there. There are no issues with sea sickness, and no cancelled dives due to big waves.

The shallow water is usually warmer as well. While I always wear my dry suit for boat dives, I dive my 5mm wetsuit year-round off the shore. A boat dive typically takes up at least half of a day, requiring you to be at the dock before 6 AM, and not returning until the afternoon. Shore diving can be done in an hour, with plenty of time to enjoy other topside activities with your non-diving friends and family.

Night diving is an incredible experience - animals that hide during the day are out and about after sunset. Bioluminescence is also amazing, and I have seen this in New Jersey. The charter boats very rarely do night dives, but when high slack tide lines up with a reasonable time of the evening, try a night shore dive. Dawn and dusk diving is also an option when the tides are right, it's a lot of fun to watch the undersea world wake up.

One issue with shore diving is that most of them are tidal in nature. While there are a few dive sites directly off the coast in the open ocean, most of these have been covered with sand in recent years, and there is little sea life on the open sandy bottom. Therefore, our shore sites are typically ocean inlets, where the clear sea water floods upstream twice a day, giving the best dive window with minimal current, greater depth and better visibility at “high slack." We are not concerned with low slack, as the water is generally dirtier, with poorer visibility due to the bays and estuaries draining into the site.

Any shore diver should have an app that shows the local tides. Also, the pages below have the tide tables embedded in them for each dive site. Depending on the location of the site and the width of the inlet, getting in the water at the wrong time can be anything from barely noticeable to a significant risk of catastrophe. I will go over specific dive sites later on in this article, but for the most part, it is best to plan your dive around slack tide, both for safety and for visibility.

Tidal water motion follows a cycle, which repeats twice each day. High tide is when the incoming sea water results in the greatest depth, and low tide is shallowest. Slack tide just means that the water stops moving in or out, and there is no tidal flow at all. Generally, high and low tides correspond with slack tide – the ocean floods inwards upstream, raises the water level, and then flows back out to sea with the water level dropping until low tide is reached.

However, there are some situations related to local geography where high tide and slack tide are at slightly different times. In some cases, the tidal station (where the tides are observed for the purpose of creating the tables) is different than the dive site. The more you dive a particular location, the more familiar you will become with these subtle, yet very important, nuances.

Tidal water flow is inversely proportional to the width and depth of the channel. Since the same amount of water has to move through all parts of the inlet during any given time period, it moves faster through narrow passages. An example of this at the Jersey shore would be the Manasquan River railroad bridge, where the streambed is narrow between the abutments. This means that a diver who stays long past slack tide will be squirted eastward at high speed past the piers as the current builds. On the other hand, the Belmar Back Bay is very wide, so the current is rarely an issue, no matter when you enter the water. For some dive sites (like the Shark River jetty), miscalculating your dive timing can mean being swept out to sea.

Typically, you want to plan your dive so that you enter the water as the tide is still flowing upstream, maybe 20-30 minutes before high slack. That means that you will have about an hour, centered on the still water of slack tide, with a small amount of current before and after that. If you need to swim against the current, you will have an easier time of it.

Some of the New Jersey sites (like the railroad bridge or the Belmar Back Bay) are open to divers 24/7, 365 days a year. For others with heavy boat traffic, diving is not allowed during peak boating hours. On Long Island, the three tidal sites (Beach 8th Street, Oak Beach Marine Park, and the old Ponquogue Bridge) all border active boating channels. While diving is not restricted here, situational awareness is paramount.

Site access can vary. The Jersey shore really welcomes divers; there are no issues with parking permits. Street parking is available and safe, and some sites have parking lots. Local groups have even built equipment tables at some of the Jersey sites specifically for divers, to help people gear up. At Ponquogue Bridge on Long Island, parking permits are required due to the proximity to the main bathing beach for Hampton Bays.

While local ordinances vary from town to town in New Jersey, there are a few that pertain to diving that are important to know. In general you are required to tow a surface float with a dive flag, to alert boat operators of the presence of a diver in the water. They in turn are restricted from operating near such a flag.

I prefer a foam float with a tall flag stick for best reliability and visibility - an inflatable float can be punctured and is not as easily seen. I use a small reel to tow the float. This is much better than the cheap plastic frame that comes with many of these, for quickly releasing or tightening up the line, and for adjusting the length of the tow underwater. To keep both of my hands free, I lock the reel and clip it off to a hip D-ring with a bolt snap. If you do this, put a "breakaway" in the line in case the flag or the line gets snagged by a passing boat. A tank O-ring works perfectly for this, just tie the reel to the O-ring and the O-ring to the bolt snap.

In New York state, not only does every municipality that borders the ocean have ordinances AGAINST Scuba Diving, the sport is also outlawed in the entire state park system. However, each regional park system can make their own exceptions to the rules. The Long Island Region does have a “Regional Scuba Permit” for diving in 4 of the State Parks on Long Island.

While the shore dive sites sometimes have excellent visibility, this is the exception rather than the rule. That doesn’t mean you can’t have a great dive on most days. Even on days where visibility is particularly bad, I have had a lot of fun doing “muck diving” to photograph the smaller residents of the area. If you like, there are some online groups where people routinely post visibility reports so that you can make a decision before driving to the site.

Macro photographers and other divers prepared to explore the nooks and crannies of these healthy, vibrant marine environments will not be disappointed. In late summer and early fall, not only are the sites dripping with life, but many tropical species which come north on the Gulf Stream can be found. Visibility is often much better in the cold weather of winter and early spring, but there is less obvious sea life to be seen at those times.

Like for all NYC area dives, two cutting devices should be carried, as you may encounter discarded fishing line and other entanglement hazards. I recommend a trauma shears carried on a harness or other BC attachment. These are cheap and incredibly strong – they can cut heavy rope or wires. Unlike a dive knife, they can be used with minimal risk of injury, even in a panic situation. As a backup, I carry a Trilobite line cutter on the wrist strap of my dive computer. Remember, you may well be sharing a dive site with people who are fishing, and those lines and hooks can end up in your path. It’s not common, but it is possible to get snagged – it happened to me.

Nitrox is unnecessary for these dives, depths are typically less than 20 feet. While a redundant gas supply is often used on boat dives in our area, this is generally not needed for shore diving given the proximity of the surface. A light is a good idea, as there are plenty of small holes to explore. And if you are diving in an area where getting swept away on the current is a potential risk, carry signaling devices (such as a whistle and/or a rescue GPS). And a mesh bag can be useful to help you carry any trash or artifacts you might pick up.

Finally, a compass is very important - it's easy to get lost or disoriented when you aren't on something like a big wreck. While you can navigate by sensing the current, watching the falloff of the bottom depth or following undersea structures (like the inlet seawall), a compass will help you find your way home and avoid ending up in an active shipping channel.

I lock my wallet and phone in my car using the waterproof "valet key" which is detachable from many modern electronic key fobs. I just put the key in my bathing suit pocket, under my wetsuit, where it can't get lost. For people who have electronic keys and no valet key option, the options are to bring a reliable waterproof case (be sure it's secure!), or hide your key somewhere on or near your car.

A supply of fresh water is useful to shore divers, to rinse off sand before loading your car, as is a small tarp or beach mat to stand on while suiting up and gearing down.

Now let’s go over some specific dive sites! Click on the photos below for information and tide tables for sites on the Jersey Shore and Long Island. This site describes the ones that we have the most experience at, but there are a lot more than these if you want to explore. Club member Danny Rivera has an excellent book on diving on Long island, as does former club president David Rosenthal. For New Jersey sites, check out the book by Daniel and Denise Berg, or the one by Tom Gormley and Ben Gualano.

SHORE DIVING VIDEO

Here is a little "sizzle reel" about the diving at the Manasquan River Railroad Bridge in Point Pleasant, New Jersey.

Here is a little "sizzle reel" about the diving at the Manasquan River Railroad Bridge in Point Pleasant, New Jersey.

This website is meant to help divers who are new to diving in the New York City area to become familiar with the specific practices, culture, gear and conditions commonly encountered here. It is NOT meant to be a substitute for formal training and certification with an appropriate instructor and agency. Every diver is responsible for their own equipment, dive planning and safety.